Arts in Review: WIFE’s Abaddon

Review and Interview by Drew Denny, Photos by Charles Mallison and Nina McNeely

Welcome to your wildest dreams!

White-haired Victorian triplets nuzzle mouthfuls of soil over the chest of a guilt-ridden man as evil incarnate belly-laughs from stage left across from two frozen Statuettes awaiting their turn inside the world’s largest magic lantern while our anti-heroine greets her tripled reflection, suddenly mounting her own vanity.

In WIFE’s Abaddon, pleasure and pain are one. Motion is imposed upon bodies as often as it springs forth from them, and the audience enjoys a full-body/full-mind exploration of the spirit world that captivates our collective unconscious as much now as it did in the late 1800’s. Abaddon reminds us that there are realms best explored via representation, ideas best articulated through artifice – Abaddon’s possession, madness and formally spectacular celebration of darkness are excellent fodder for the winter of the Apocalypse.

A designed experience from the outset, Abaddon exists for two weekends inside of a theater constructed within a giant loft in Boyle Heights. Seats buried in white cloth, candles flickering upon a dusty old organ, and rolled up wax-stamped programs inked with the evening’s recipe welcome a packed house to an understated underworld: A stark stage draped in more white punctuated by a bureau, a chair, and a round pedestal garnished by two motorized hanging lanterns inhabited by lithe dancers in avant-couture textiles, wigs and makeup. A score of beats and distortion accented by sighing wine glasses and wailing pipe organs slithers and throbs through the audience and performers alike while projected footage of dancers flying and drowning washes over the space like the lucid dreams of an incarcerated poet.

Abaddon embodies the most creative exploration of eroticism that I’ve seen of late – trapped by vanity, our female lead mounts her bureau and leads her three reflections in chaotic rounds of gaze and gesture. Woman is possessed! Demonized for her desires, she stutters and gyrates – twitching and stumbling hither and thither, I believe her with all my being and marvel at the control required to perform the state of having no control over one’s own limbs. She spins round and round, abandoning her agency like a snake molting old skin Abaddon’s excellent employment of furniture is reprised with the best chair dance I’ve ever seen as the male lead drags his chair across the floor by his pelvis, a half-man half-décor Centaur.

Possessed woman approaches far wall and bursts into flames.

Silvery cheekbones, powdered teeth, three heads moving as one.

I can’t understand the libretto but I don’t care.

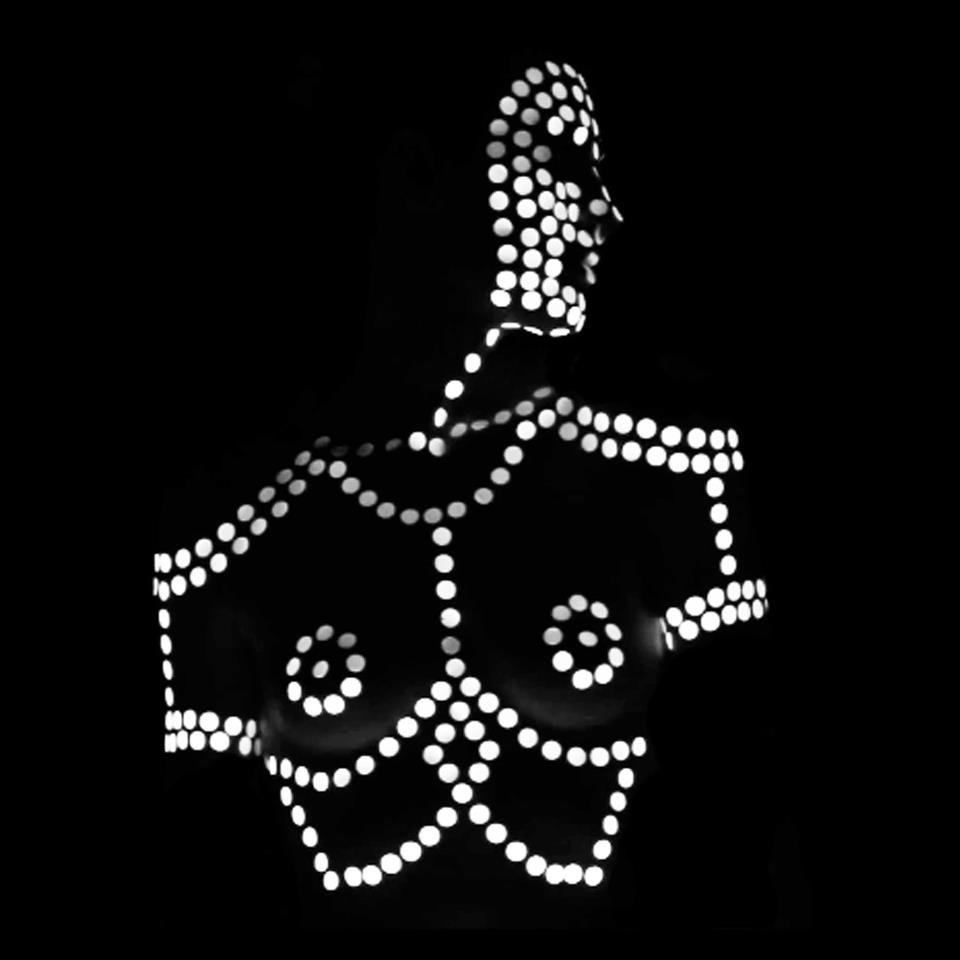

In a piece so dense with corporeal and technological reference, the simplest trick delights the most. Enter the meta magic lantern – two Statuettes pose upon a platform while two lanterns swing in a circle around them. The choreography captivates, and the shadow-play is absolutely mesmerizing. What visceral pleasure! Re-enter the trance of childhood when a moving light can be the most beautiful thing you’ve ever seen… until you notice the shadows its casting. . . Within bodies, upon bodies, between bodies – light and shadow follow their own choreography inscribed by projected images created in the dance studio using a giant fan, in-camera effects, and CGI.

Abaddon ends with a blissfully minimalist crescendo as the cast approaches the audience during the black moments of a strobing light… Closer… Closer… Closer… the end!

Interview with WIFE

by Drew Denny

How did you come up with the concept for Abaddon?

Leahy: We were inspired by a specific period of history in America (the late 1800s) and the storytelling devices used then. It started with a discussion of shadow, which led to exploring tricks with light that were used in theater/storytelling at that time – magic lanterns, the first “video” projectors, and Pepper’s ghost. We thought it would be exciting to use modern technology in an old way, to make it feel like something that was created then. We are always influenced by stories, and a lot of the stories told then dealt with ghosts, death, the macabre. There seemed to be a fascination with spirits, witches, madness, possession. We wanted to explore these themes that are present at all times in all cultures in this 19th century American way (but with a bit of Japanese influence, which somehow always finds its way into our work). As a collective, we are obsessed with fairy tales, history, mythology, lore. We wanted to explore the darker side of these themes that coincided with the aesthetic we were creating. Abaddon is an ancient Hebrew word for a purgatory – a place of destruction. This is the place where our characters live.

What does Abaddon say about sex and eroticism?

Jasmine: For this particular piece we tended to avoid overt sexuality. Much of the choreographic process was spent eliminating sexuality altogether. We wanted to celebrate the beauty of darkness, the beauty of revealing ugliness. In Deena’s (the Heretic character) second solo, for example, the devil (the Holy Sleeper character) has gone inside her and is stimulated by how it feels to have a woman’s body. She is exhausted physically yet spiritually aroused and self-obsessed. Historically speaking, Deena represents a sexually advanced woman, deviant from the conservative Victorian norms of female behavior. She is classified “mad” by her unruly desires: she is physically and mentally fucked by the Holy Sleeper.

The Wives are asexual. Having been dead so long, we find stimulation in dirt, the one tangible element we can touch from earth. Steven (the Lonesome Man character) is the only living character in the piece after Deena burns to death. Driven by so much curiosity and angst, his sexuality is muted by layers of guilt and psychological turbulence.

There are no sexual conflicts in Abaddon. Pleasure and pain bleed into one. Stimulation lives among the memories of touch. The erotic belongs only to the lord of death.

How do you represent insanity in this work? Do you believe in sanity?

Nina: We wanted play with different stages of insanity and where it could have stemmed from for each character. The lead male Steven Synstelien’s insanity was based on a longing and searching so obsessive that he became lost in hallucinations and delusions resulting in his final unfolding. The lead female Denna Thomsen’s character was based off the 19th century stories of so-called demonic possesions and their relationship to how society views female sexuality. The Statuette characters Reshma Gajar and Justine Clark represent insanity from emptiness, loneliness and the horror of being frozen in time.

Who produces your video projections? What’s it like to interact with light during a dance?

Nina: I created the video projections in Abaddon aside from the opening sequence edited by Darwin Serink. For this project we teamed up with a group of videographers: Joshua Harran, Sarah Harron and Darwin Serink to create our own original content. Utilizing a combination of pre-CGI camera tricks and CGI post effects we created imagery involving dancers flying through the night sky and drowning deep into the underworld. We shot everything in a dance studio with lots of black material and a wind machine. We wanted to use the video aspect of the show to intensify the mood with imagery and tell the back-story of the characters. Interacting with light during dance is like dancing in a living and breathing landscape, one that is also choreographed. We chose dancers who are also great actors to breathe life into the faux environments and ghostly characters projected in the show.

How does WIFE operate practically in order to produce such large scale, high concept, highly produced events?

Jasmine: Many factors went into producing this particular show. To begin, we received a Durfee grant that allowed us to buy a projector. This was a major upgrade considering that we’ve borrowed a projector for all our previous performances. We then created a Kickstarter to raise funds for the cost of converting an empty loft into a theater and to pay our fellow performers and collaborators. We could not have done this without the immeasurable help of Quinn, our tech husband, so to speak. Conceptually, the three of us started meeting on a regular basis to throw out ideas for the story, the myths that inspire us, the ideas that haunt us, the images that move us. Faust and Metropolis set the inspirational tone for an atmosphere of purgatory: a lonesome, possessed dusty existence where time is lost; a place where the spirit world intertwines with the mundane and centuries lost. Abaddon was born out of a desire to go back in time, technologically and aesthetically to a place where people entertained before electricity, before computers, before fancy graphics, and to create a 19th century-inspired ghost story. We studied Pepper’s ghost, magic lanterns, and other old fashioned tricks of the stage. We shared our ideas with the musicians and asked them to create music that sounded dark, using instruments such as wine glasses and pipe organs. We then began choreographing while meeting with Cati Hawkins to discuss the nature of the set and our desire for a gaunt, uncomfortable yet beautiful haunted mansion look. We also conducted four different shoots to collect footage for the projections with the help of many friends: the Harrons, Hunter Hamilton, Darwin Serink, Adrian Gilliland, and Nathan Moss. Lou Becker, our producer, took notes while we ran through the show and kept us on time. He really pushed us into fifth gear during crunch time and transformed the audience space into a death palace. Brian Getnick, director of Native Strategies met with us to discuss the cognitive roots of the piece.

Who created the score? The music is incredible!

Jasmine: Robbie Williamson, Rodrigo Amarante, Oscar Santos, and Dorian Wood.

What about costumes? Hair and makeup? What were your inspirations?

Jasmine: The three Wives dresses were created by Ryan Heffington and Mindy LeBrock. The Statuette costumes were created by Cathy Cooper, who also helped style Deena, Steven and Dorian’s look. We were inspired by these 19th century albino photos that Nina shared with us. We wanted lots of material, long draping sleeves, and some sort of Puritan conservative coverage in the front. Simple and dirty. The wigs were designed by Franc Fernandez and Bethany McCarty helped with make-up.

Who created the set pieces?

Leahy: Cati Hawkins is our set designer, and she constructed a lot of the sets. The boxes were made by Steven Synstelein, our “Lonesome Man,” which we used for our previous piece The Grey Ones (watch video) and repainted for this.

How did you come up with the magic lantern idea?

Leahy: We were looking for a way to create moving shadows on the walls like a magic lantern does. We enlisted the help of our friend Derek Michael, who is a tech/lighting/inventor genius, and brainstormed a way to create a moving light source that would circle around and shine on the three Statuette characters perched on boxes. He created the installation with a motor he already had and added these found old lanterns with battery powered LED lights inside.